- Home

- Abdelilah Hamdouchi

Whitefly Page 2

Whitefly Read online

Page 2

Allal quickly put the beads back in his pocket. He seemed to be having a hard time leaving his inner thoughts behind.

“The ambulance is late,” said the inspector absentmindedly.

“Why don’t you radio them again?” asked Laafrit.

Allal lowered his head and walked toward the car. Laafrit leaned over the corpse.

“No need to dirty your hands,” said Abdellah. “They call themselves harraga, the people who try to cross illegally, because they burn their IDs before setting out on the patera so that no one will know who they are or where they came from if they get caught. This guy isn’t any different from the rest.”

“Everyone knows that,” said Laafrit, continuing to inspect the body. “At any rate, this poor son of a bitch and his buddies took a wrong turn. Maybe they had a crooked compass or just some bad luck. They should’ve washed up in Algeciras. They’d have made it to paradise, even if they got there DOA.”

Laafrit finished searching the corpse’s pockets and wiped his fingers in the sand. When he got up and looked at the car, he was annoyed to see Allal sitting inside with the heat on.

“I’m not happy with him these days.”

“You’ve got to keep in mind everything that’s happened to him, Laafrit. Leave the guy alone.”

“All this because he joined that group of Sufis?”

“I myself go with him sometimes,” said Abdellah, as if revealing a secret. “There are rituals, like dhikr, hadra, amdah, and banquets. Can’t you see I’ve gotten fat? I used to be weak, but the remembrance of God whets the appetite more than any glass of wine. It bestows tranquility and calms the heart.”

The Dwarf’s unusual eloquence confused Laafrit and grabbed his attention.

“Are you trying to recruit me too?” asked Laafrit.

“Come at eight o’clock. At least fifty people will meet up at the villa of a rich man for a banquet after dhikr and amdah.”

“I can understand Allal,” said Laafrit. “But did you have prostate surgery too?”

“This is sheer disinformation, the result of ignorance,” said Abdellah, lifting his hand angrily. “The prostate is the equivalent of a woman’s womb and by simple deduction, it’s clear that just as woman doesn’t desire man with her womb, man doesn’t desire woman with his prostate.”

“Where’d you get that from?”

“I asked an herb doctor.”

Laafrit laughed.

“You should ask Allal,” he insisted.

Abdellah leaned toward Laafrit.

“We’re the ones who caused his depression and made his situation terrible. He knew what we were saying behind his back and this affected him a lot. But the truth is simple. Allal didn’t lose his manhood during the surgery. Instead, he saw death close up so he decided to get to know his Lord. He went on the hajj and found what he was looking for with the Sufis. He took the lesson he learned to heart.”

The ambulance siren in the distance jolted them back to reality.

“Take off his jacket,” Laafrit commanded.

Abdellah looked disgusted. He hated touching corpses, even though he’d been in this line of work for more than twenty years. While Abdellah was hesitating, Laafrit took a long look at the body and, for the first time, had a funny feeling about it. This one seemed different from the others, as if the expression of death had been traced on his face before he drowned. His long hair was knotted on top of his head and despite it being covered in sand, it looked thin, obviously the kind of hair that didn’t need a comb. What clearly distinguished him from the other drowned bodies that had washed up this week were his new clothes. They caught Laafrit’s attention because they were totally inconsistent with the cheap clothes harraga typically wore.

Laafrit took a deep breath. He wasn’t sure whether he should pay special attention to the guy’s appearance or ignore it, but he found himself bending over the corpse, checking it out at close range. The forensics agent moved away.

“I’ll inspect him,” said Laafrit.

He took prints from both hands. Laafrit couldn’t get the wet zipper of the jacket open, so to speed things up he lifted the jacket over the torso and kneeled down to look at the body.

Laafrit’s face went pale.

He let out a whistle. Abdellah came over and also dropped to his knees. He pressed on the corpse’s stomach with his fingers and began counting.

“The first one in the heart, the second below the liver, the third in the stomach, the fourth—”

Laafrit didn’t give him time to finish. He pulled the jacket and shirt off the body.

“The fourth,” the forensics agent went on, “pierced his right side. We can’t exclude the possibility it passed right through him.”

Abdellah got up, reeling, and pulled out his camera again. While he was taking a bunch of photos, Laafrit lifted the leather jacket and examined it closely.

“It seems he wasn’t killed,” said Laafrit. “He was executed.”

Abdellah looked at him, confused.

“No bullet holes in the jacket.”

Abdellah pursed his lips the way he usually did when he didn’t get something.

“The killer emptied a gun in him and then put his jacket on,” said Laafrit.

“Any more surprises?” asked Abdellah.

Laafrit turned the corpse over and saw his back was unscathed. Abdellah tightened his lips and resumed taking photos.

“This isn’t the corpse of a harrag. We’re looking at a murder and, most important, it was committed with a gun,” said Laafrit.

Wearing a look of exhaustion, Abdellah didn’t even try to add anything. He just stood there next to Laafrit as the two contemplated the savagery of death, with the rough sea in the background.

The corpse was rushed to the morgue. When the Criminal Investigations Unit made it back to the station at five thirty, Laafrit had a hard time getting through the corridors to the commissioner’s office. They were filled with dozens of people who had been arrested at the demonstrations at the employment office. Some had visible wounds from the cops’ violent intervention. There were some children there too, crowded together in a sitting room. They were put far from the offices so they wouldn’t annoy the police with their crying. Laafrit stopped in front of them.

“Even they were demanding work?” he asked a uniformed cop.

The cop smiled and walked ahead of Laafrit to open the commissioner’s door for him.

“These little shits were pelting us with rocks,” he said.

Laafrit glared at them provocatively.

“A hundred lashes on the rear for each one!” he yelled, feigning seriousness and trying to scare them.

The kids’ cries turned to screams. The cop let out a laugh, baring his rotting teeth.

The commissioner’s office was wide, with a large window overlooking the city’s pearly lights. The desk, chair, and other furniture evoked the unspoiled air of Tangier from its international-zone days. Everyone said the furniture should have been in a museum but had been sent to the main police station instead, due to budget cutbacks.

The commissioner stood up abruptly to greet Laafrit, despite his lower rank. Their relationship didn’t follow the normal protocols.

“I heard today’s drowning victim was shot to death,” he said.

The commissioner couldn’t hide his shock, and was still in denial about what had happened.

Laafrit swallowed the lozenge in his mouth and gave the commissioner the details. The commissioner kept silent, though his excitement was evident.

“Where’d the negotiations with the prefect lead?” asked Laafrit, taking advantage of the opportunity to ask about the unemployed university graduates, and hoping for some praise.

“I’ve got no idea. They’re still meeting. All that matters for us is that the demonstration’s over.”

Laafrit relaxed in his chair and rubbed his belly.

“And everyone in the corridors?”

“We’ll release some and charge

the rest.”

“What about the kids?”

“We won’t let them go until their parents show up.”

Laafrit felt like the demonstrations were ancient history.

The commissioner carefully set his pen on his desk and then quickly brushed it aside. He wasn’t deep in thought as much as he was enraged.

“Four drowned bodies in less than three days, one full of lead,” said the commissioner, as if trying to convince himself of the situation. “What does it mean?”

“It means we’re standing in front of a mountain of work,” said Laafrit in frustration.

“What lead should we follow? Smugglers, harraga, or what?” asked the commissioner, his features tightening.

“In my opinion, the two intersect,” said Laafrit. “My first impression about the drowned bodies is they’re harraga. All evidence points to it, but what doesn’t make sense is the one who washed up shot dead. He didn’t even look like a harrag since his clothes were new and expensive. And it’s incredible the bullets didn’t go through his jacket—”

“Could he have gotten mixed up with harraga by accident?” asked the commissioner, cutting him off.

“Hard to say. We’ve got to wait and see if the sea spits up any more bodies. Pateras only set out if they’re crammed with twenty or thirty harraga.”

“Does the murder victim look like he’s been in the sea longer than the others?”

“Not much.”

The commissioner was disgusted and a look of loathing appeared on his face.

“If a boat full of harraga went down, it definitely happened near our shores,” he said.

“So far,” said Laafrit, who was at a loss, “we haven’t gotten any news of a patera sinking.”

The commissioner put a hand over his mouth and yawned with exhaustion.

“If a boat went out,” he said, “it wouldn’t have left from the beaches around Tangier. The patrols are too heavy there. Even the fishermen help us out. But who knows?”

The commissioner let out a desperate sigh that sounded more like a moan.

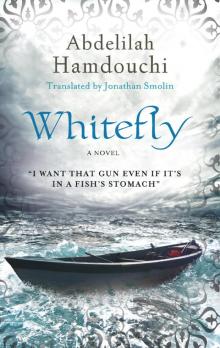

“I don’t give a shit about harraga,” he said bitterly, waving his hand suddenly. “I want the investigation to concentrate on the gun. Where’d it come from? How’d it get into the country? Where’s it now? I want that gun even if it’s in a fish’s stomach.”

These fits weren’t unusual for the commissioner. They indicated his blood sugar was low.

They heard a knock on the door and then it opened. A uniformed cop appeared and they could hear the kids’ screams and crying behind him.

“Is this a fucking daycare center?” yelled the commissioner.

The cop was confused and hesitated. He looked over at Laafrit.

“Sorry to disturb you, sir. Detective Laafrit, could you tell the kids we’re not going to whip them? They haven’t stopped screaming and crying since you left.”

2

THE NEXT MORNING, LAAFRIT FOUND the medical examiner’s report on his desk, together with a plastic bag containing the three bullets extracted from the victim’s body and a description of their trajectory showing the murder victim took the shots from the front at very close range. As for the two bodies from the day before, the autopsy established they died from drowning, just like the first one, which had washed up two days ago. The report posited they’d all been in the water for between one and three days.

Laafrit tossed the report aside. It was hastily written, lacked precision, and didn’t shed any light on the investigation. He picked up the phone and called the medical examiner. After the fourth ring, he heard Si Abdel-Majid’s voice, indolent as usual and laden with formalities.

“Professor Abdel-Majid from the Autopsy Division.”

“Good morning, professor,” said Laafrit cheerfully, trying to lighten the formalities.

“Good morning. I sent you the report on the drowned men. There is only one problem. I don’t know how the shooting victim wound up with them.”

“We don’t know either. I’d take your report seriously if it actually helped us develop a single lead—”

“I carried out my job as required,” said the medical examiner, cutting him off. “If you had read my report attentively, it would have been easy for you to understand that the murder victim took the bullets in vital organs, except for the one in his side that didn’t cause a mortal wound. As for the others, they died from drowning and there are no signs of violence on them.”

“That’s clear from your report,” said Laafrit, annoyed with Si Abdel-Majid’s arrogance. “If you would, I’d like an analysis of their stomach contents.”

“For the shooting victim too?”

“For them all. Thank you.”

The detective hung up quickly so as not to give the medical examiner time to object. He put the first lozenge of the morning in his mouth and then called Abdellah into his office.

It was clear Laafrit hadn’t slept enough. He kept yawning and rubbed his eyes, which were surrounded by dark rings. Laafrit didn’t like the taste of the lozenge so he took it out of his mouth and put it in the ashtray.

Abdellah came into Laafrit’s office with a pale face, clenching his teeth. Laafrit glanced at him and told him to sit down.

“Something wrong?”

Abdellah shook his head.

“My stomach,” he said, in a voice interrupted by groaning. “I haven’t slept a wink. Every time I leave the bathroom I’ve got to run right back.”

“Allal complained about the same thing,” said Laafrit, with a look of surprise. “He asked for permission to go to the pharmacy.”

Suddenly he hit his forehead as if he’d just remembered something.

“Did you two go together to the banquet yesterday?” he asked.

“To the circle of amdah and dhikr,” said Abdellah, correcting him in a weak voice. “At a circumcision party, I ran into a gentleman who honored us with a banquet unlike any other.”

Abdellah forgot his ailment and continued talking exuberantly.

“A couscous you eat with your fingers because of its incredible deliciousness. Afterward, tagines with lamb and plums, then chicken with olives and pickled lemons. We broke up the meal with filali sweets and then had plates of all kinds of fruit. But what gave us diarrhea were the cups of milk mixed with rose water.”

Laafrit looked at him suspiciously.

“Okay, I’ve got other things to do than sit here listening to stories of Ashaab al-Tamaa, the unwanted dinner guest,” he said. “Take these things in front of me and add them to the fingerprints. Send everything to the crime lab in the capital.”

Abdellah took the bag with the bullets and looked at it carefully. He stared at the medical examiner’s report and was surprised to see it was only a few lines long.

“What does Professor Abdel-Majid have to say?”

“When you recover, we’ll talk,” said Laafrit despondently.

Abdellah’s face twitched and thick beads of sweat glistened on his cheeks. He sat pinned to the chair as if something serious was preventing him from getting up. Laafrit looked at him perplexed.

“Sorry,” said Abdellah weakly.

He left the office and ran to the bathroom.

Laafrit went downstairs slowly. He didn’t notice the greeting of the guard brandishing his machine gun at the station’s entrance. The detective stood on the sidewalk and looked up at the sky. It was a beautiful day with a clear sky and light, warm winds. Yesterday’s rains had washed off the streets and trees.

Laafrit looked at his watch. It was now ten thirty and nothing was moving in the case except for a lackluster report from the morgue. If things kept going this slowly, Central would send in a special unit to take over. That was the last thing he wanted.

Laafrit thought about going to the café across the street for a cup of coffee but he reconsidered. If someone saw him there, they’d think he was on vacation, and at a time like this. Finally, the black Fiat pulled up in front of him. Inspector Allal opened the door and La

afrit got in, hiding his anger.

“Please don’t tell me I’m late,” said Allal. “The tank was empty and I had to stop for gas.”

Laafrit cringed but kept silent. He knew he needed his assistants today and any tension between them might undermine their work. He pretended to be in a good mood.

“How’re your intestines now?” he asked.

“Fine. That banquet cost us a lot,” Allal said. “But it was worth it.”

Laafrit feigned interest.

“The Dwarf told me cups of milk mixed with rose water were the culprit,” he said in a tone filled with derision.

Allal glanced at the detective, but all of a sudden he fixed his eyes on the road as a black Mercedes driven by a man with an ugly face cut them off. Allal slammed on the brakes, which let out a screech. The car shuddered. Laafrit shut his eyes as a kind of madness hit the inspector, who began cursing, almost jumping out of his seat.

“Let’s get him!” he screamed. “Do you give the order?”

“No,” said Laafrit. “He had the right of way.”

Rage dissipated from the inspector’s face and calmness unexpectedly took its place, as if he’d outsmarted his nerves.

“There is no power and no strength save in God,” he repeated several times.

He drove through a number of side streets and stopped to let an old woman pass in front of the car. He was careful to slow down while moving behind a bus, even though he could have easily passed it. Laafrit got annoyed. He thought this meekness on the road was in response to him not letting the inspector go after the Mercedes.

“Stop at the newspaper kiosk,” said the detective, irritated.

Laafrit got out of the car, leaving the door open. A few minutes later, he came back with a stack of Arabic and Spanish newspapers.

“Hurry up,” he told Allal. “We’ve got to get to Ksar es-Seghir before noon.”

Laafrit flipped through the papers. There was no news at all about the negotiations that had broken up the demonstration of the unemployed graduates, even though the front pages of all the papers highlighted the cops’ violent intervention against the crowds in front of the employment office. He flipped through the rest of the papers carefully but found nothing in either Spanish or Arabic about a sunk patera. A strange front-page headline, however, made him smile. Laafrit read it aloud:

Bled Dry

Bled Dry The Butcher of Casablanca

The Butcher of Casablanca The Final Bet

The Final Bet Whitefly

Whitefly